History of the Byron White Courthouse

Building History

Colorado Territory was officially organized by an Act of Congress on February 28, 1861, out of lands previously part of the Kansas, Nebraska, Utah, and New Mexico territories at the end of President James Buchanan’s term. During the term of President Abraham Lincoln three separate districts of the Colorado territorial federal courts were established in Denver, Central City, and Canon City.

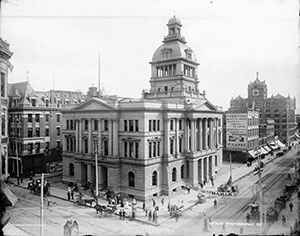

The Denver District Federal Court, covered the area east of the Rocky Mountains. Court was convened in September of 1861 in Denver in the Commonwealth Building on Larimer Street. After moving through a variety of commercial locations, the U.S. Treasury Department built the original Denver Post Office Courthouse on the south corner of Arapahoe and 16th Streets (1884-1886). Diagonally across from it rose the 20-floor Denver landmark Daniel & Fishers Tower. The post office courthouse was done in the Second French Empire architectural style.

The Denver District Federal Court, covered the area east of the Rocky Mountains. Court was convened in September of 1861 in Denver in the Commonwealth Building on Larimer Street. After moving through a variety of commercial locations, the U.S. Treasury Department built the original Denver Post Office Courthouse on the south corner of Arapahoe and 16th Streets (1884-1886). Diagonally across from it rose the 20-floor Denver landmark Daniel & Fishers Tower. The post office courthouse was done in the Second French Empire architectural style.

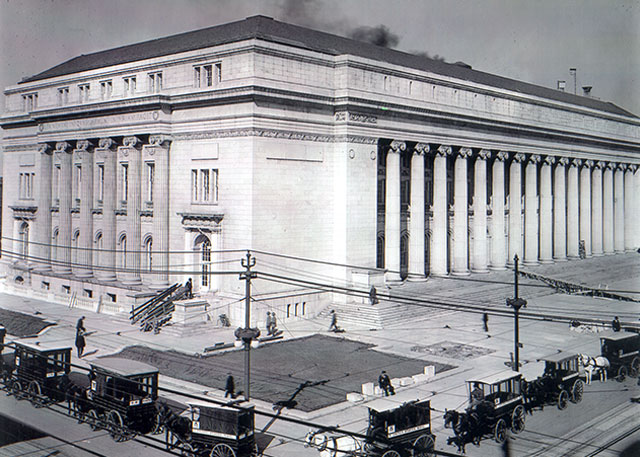

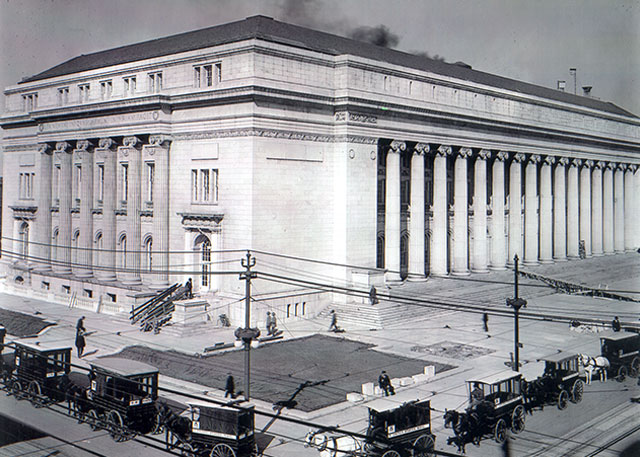

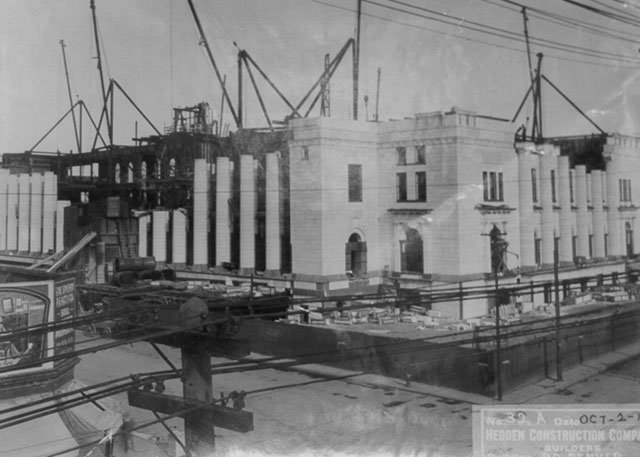

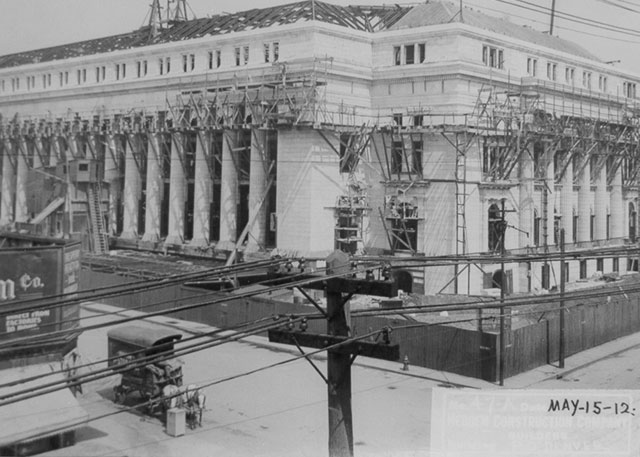

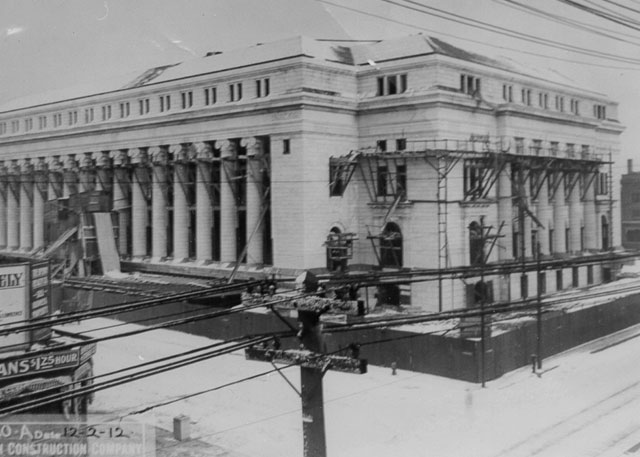

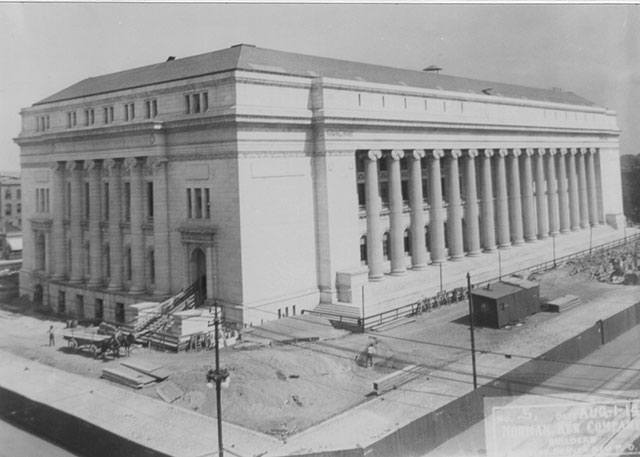

When this building became too small and less functional for the federal offices within, the Treasury Department built between 1910 and 1916 and located at the corner of Stout and 18th Streets. This post office courthouse was designed by the New York firm of Tracy, Swartwout and Litchfield in the Neoclassical or Classical Revival architectural style. Symmetrical design, grand classical stone columns, and monumental stairs characterize this style. At the time it was one of the tallest structures, and considered the most beautiful building west of the Mississippi.

The four-story, marble building takes up an entire city block in downtown. The main entrance facade features 16 three-story columns. On the interior, the impressive main lobby, along the Stout Street side, spans the width of the building. Along the 18th and 19th Street are significant side lobbies connected with the main lobby. Upon major renovation of the courthouse, in April of 1994, Congress approved its renaming to the Byron White U.S. Courthouse.

The original budget for the building was $1,500,000, but was raised to $1,900,000. Upon completion in 1916, approximately $2,586,000 had been spent by the federal government. It was designed and was built for the Post Office occupying mainly the first floor, the U.S. District Court and the U.S. Court of Appeals occupying the second floor. As depicted in the 1909 drawings, the third and fourth floors were occupied by other federal offices, such as the U.S. Marshals, the Secret Service, the then-named District Attorney (now U.S. Attorney), the Immigration Offices, the Naturalization Office, the Land Office, the Customs Department, the Railway Mail Service, the Geological Survey, the Reclamation Service, the Internal Revenue, the Forestry Service, the Civil Service, , the Pension Office, the Office of Animal Industry, and the Weather Bureau. A platform on the roof housed the instruments for the official weather station of Denver.

Architectural Style

Architectural Style

April 1911

May 1911

July 1911

October 1911

February 1912

May 1912

December 1912

August 1914

Although not the first neo-classical building in Denver, its design introduced and popularized this style on a grand scale. Original plans specified the use of Georgia marble, but through the efforts of local businessmen, the native stone “Colorado Yule marble from Marble, Colorado, was used to clad the exterior of the post office courthouse. The Lincoln Memorial and the Tomb of the Unknowns in Washington, D.C. have also been clad with marble from this quarry. The interior facades of the courtyards are limestone, possibly coming from Indiana. This building has been described as “a poem in marble”.

Through the years, as the federal government grew and its agencies expanded, contracted, and changed their missions. By 1964, upon completion of the Byron Rogers Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse, the building came to be mostly occupied by the U.S. Postal Service and the U.S. District Court and the U.S Court of Appeals. By 1990, as the judiciary’s caseloads expanded, its courts required larger facilities, the Court of Appeals requested that the Congress approve and appropriate funds sufficient to renovate the Denver Post Office Courthouse. The General Services Administration was called upon to renovate this building. The purpose of the renovation, completed in 1994, was twofold: To convert the entire building to judiciary functions, primarily for the Court of Appeals to accommodate four courtrooms and to the greatest extent possible conserve and restore the historic building in accordance with its status as a Colorado Landmark building, listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Beyond the basic historic restoration, renovation, and conversion issues, this project endeavored to incorporate and upgrade the building’s elevators, heating and cooling, electrical, plumbing, and security to the most current federal functional, life safety, and accessibility standards. The total cost of the restoration, renovation, and conversion was approximately $30 million dollars. This included the incorporation of unique artwork, valued at $120,000, which was guided by the Art and Architecture program of the General Services Administration. The historic building, placed within a contemporary replication context, has been estimated to be valued in excess of $200 million. As with many historical properties the initial and continuing efforts to preserve and conserve an irreplaceable historic structure realistically push the value into the priceless category.

Exterior of the Byron White Courthouse Credit: Wally Gobetz, licensed under Creative Commons

Historic buildings are not always measured by their architectural styles, decorative shapes, and materials, but also by incorporations into their architecture of the less obvious and unique: philosophical inscriptions, names of revered individuals, sculptures, and statuary used to decorate these classical structures. These are historical reminders of what was and may continue to be important. The cities incised in the marble on Stout Street’s entablature above the sixteen columns are a characteristic example: Those cities on the east of the façade are to the east of Denver and those on the west are cities to the west of Denver. These indicated the direction of mail movements to and from the City of Denver. Additionally, incised on the walls bordering these columns are the names of prior Postmasters General. The names on four interior walls of the first floor are of the most well-known of the Pony Express riders. The two emblematic bighorn sheep of the Rocky Mountains, anchoring the 18th Street entrance, are of Indiana buff limestone. These were completed in 1936 by Gladys Caldwell Fisher, a Denver sculptor, as a commission by the Treasury Department’s Public Works of Art Project.

Credit: Jimmy Emerson, licensed under Creative Commons

Grand Hall

The Grand Hall

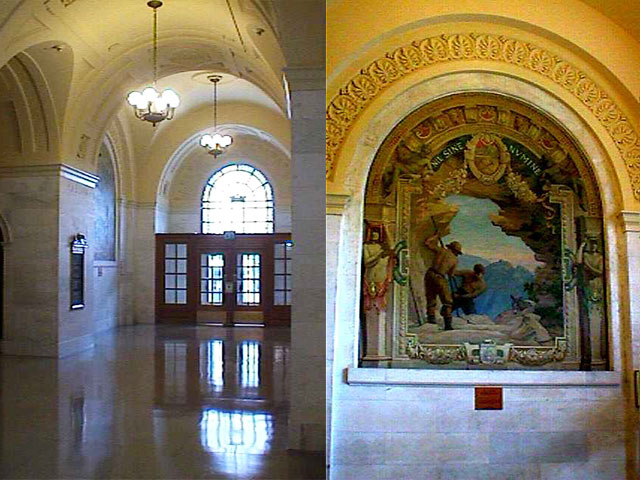

This grand hall and entry retains many of the features originally a part of the Post Office’s main lobby. The wood and glass main entry vestibule has been enlarged, but retains much of the flavor as the original, using a combination of the original design and new materials. The floor of the lobby was originally inlaid with marble and terrazzo (marble chips set in cement and polished) was repaired with new terrazzo and marble, matching that of the original materials. The vintage late 1800s Victorian chandeliers are recreations of the originals based upon historic photographs.

A majority of the interior wall along the lobby originally contained post office boxes, which over time was renovated to include the Post Office’s public counter and then upon the renovation of 1994 now includes entries to two new courtrooms and the reception area of the court clerk’s office. A section of post office boxes remain to carry through the original purpose of this lobby. The exterior wall along the lobby has been restored, including the recreated post office’s glass-topped writing ledges.

The two free-standing writing tables in the lobby were originally located near the money order division of the old post office in a lobby along 19th Street, which now houses the Byron White Historical Display. The original dark red, black and white-veined pedestals were found in the basement’s storage vaults after the renovation of the post office courthouse in 1994. Their recreation was a result of collaboration between a GSA building manager and a court employee, researching historic photos and drawings and finding pieces of the bronze bean pod filigree, bronze rosettes, and pieces of black glass. They designed, specified, and contracted with a foundry craftsman in Tulsa, Oklahoma to recreate the tables as closely as possible. This craftsman pointed out that,at the time of the building’s design and construction, architectural details and ornamentation were shared and incorporated throughout. Notably, the floral embellishments of the brackets along with the decorative bean pods and rosettes of these tables are also found in other architectural details of this post office courthouse.

The Grand Hall is completed with two lobbies serving the historical 18th and 19th Street Hallways, winding marble and brass stairways, and elevators. These lobbies display four canvas murals of Hermann Schladermundt, completed in 1918. The Tenth Circuit Historical Society and the Court of Appeals in partnership with the GSA are using the two Hallways to provide historical displays of Justice Byron White and of the Tenth Circuit’s history for public awareness and education.

Materials were chosen to reflect the dignity of the court, and with respect for the original design and character of the building. The pendant lights throughout the public corridors and the courtrooms are related in form to lights used in public structures in the early 1900s.

Historic Courtrooms & Library

Historic Court of Appeals

This courtroom is a recreation of the original courtroom. During the 1960s when the Court of Appeals moved to the courthouse at 19th and Stout Streets, this room was completely demolished to make way for more office space. A third floor level was inserted. Accounts from that period vary concerning the fate of the original architectural ornament. One source reported that the original marble columns found their way to a popular singer’s custom home in Aspen, Colorado. However, a sadder and probably more accurate account by a postal employee of the time is that the columns were simply broken up into convenient size pieces and hauled away to the dump. In the 1960s this type of space was often considered old fashioned and stuffy.

Fortunately, both excellent photographs from early years and the original drawings were available to aid in the recreation. Only the center portion of the ceiling and the very top portion of the walls above the ornate plaster entablature are original. Both of these areas required extensive restoration. The names, which are inscribed with the original gold leaf, are those of noted American judges and advocates of the law.

The decorative entablature work and columns are made of fiberglass reinforced plaster, reproduced by a small company in Jamestown, Colorado. The marble wainscot surrounding the room is newly fabricated stone from the Colorado Yule Quarry in Marble, Colorado. The heavy velvet drapery is a recreation of the original. This building was one of the first to benefit from the science of acoustics, new in 1913. The “windows” on the east side of the room are false, the drapery hiding acoustical panels, originally woven of horse hair. The original floor was thick cork with a border of marble. The new custom carpet with its lighter border follows the original pattern.

The judge’s bench is a copy of the original as is the railing (or bar) separating the public seating from the theater of the court. structures in the early 1900s.

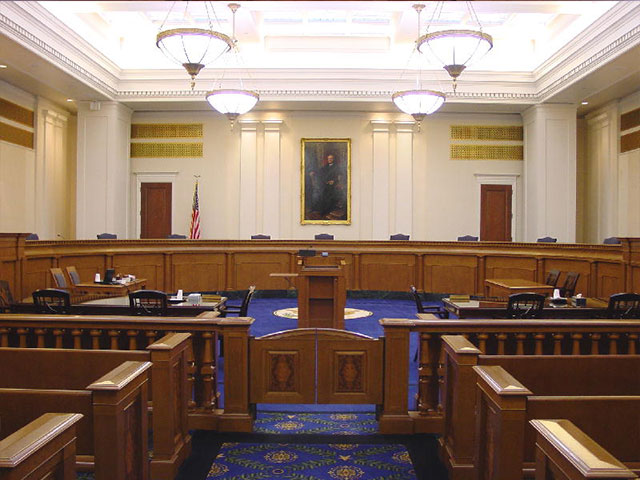

Historic District Courtroom A

This courtroom is used as a trial courtroom by the U.S. District of Colorado. It name: District Courtroom A reflects its original historic name. It was originally created for the district and has been in continuous use since 1916. It has seen some significant modifications through the years, but not to the extent that the historic appellate courtroom on the second floor suffered. The most notable modification is the raised flooring, the theater-style seating, and the boxed well for the litigants added in the 1960s to improve sight lines. The courtroom’s furnishings are not original, but were refinished as part of the latest restoration. According to historical photos and the original drawings, on display in the Tenth Circuit’s Historical Display, the original judge’s bench, jury box, and witness stand were replaced (possibly during the 1960s renovation) to meet the then-current and present courtroom’s requirements.

Although the velvet window coverings are newer, the black velvet with gold decoration on the ceiling of the apse behind the judge’s bench is original, having endured for eighty years. The chandeliers in this room are original. During the renovation of the early 1990s, the colors of the arched ceiling were lightened to match the original paint finishes used.

Historic Law Library

This grand historical space, trimmed in oak paneling, bookcases, and carved architectural detailing was the original the Tenth Circuit’s Library. The redesign and renovation caused this space to be largely restored and repurposed as a courtroom, favored by many judges, litigants, and the public for its rich and intimate setting.

It was converted for use as a courtroom. Most of the oak woodwork on the walls of the room is original, but has been completely refinished. Carved around the perimeter of the room, just below the ceiling, are the names of great legal authorities and writers from the earliest date of many nations. On either side, above the entry doors, is elaborate original carving, surmounted by a splendid full three-dimensional eagle.

The bookshelves lining the lower level are recreations of the ruined originals. However, the books are not part of the Tenth Circuit’s working collection. Instead, their primary purpose is to improve the acoustics of the room. The second balcony level once also had bookshelves. For both safety and security reasons, the second level walkway is not accessible.

All of the courtroom furniture in this space, as in the other appellate courtrooms, is new and was especially designed and made to be compatible, yet distinctly non-period, with the Neoclassical or Classical Revival architectural style of this courthouse.

New Courtrooms

Courtroom One "En banc"

This courtroom was designed and constructed, among four appellate courtrooms, in the early 1990s, as an "en banc" appellate courtroom to accommodate Court of Appeals cases, normally requiring larger groups of judges. It is not an historical courtroom, but borrows classical detailing of the era and occupies a portion of the former post office’s public counter and its workroom, housing mail handling and sorting functions. The size of this courtroom’s circular bench and its spectator seating is accommodated by moving the walls beyond the bounds of its four columns, i.e., detached columns. The ceiling is accented by a recreation of the original skylight over the post office's workroom. It is now composed of more ornate painted beams and trim and highlighted by faux onyx insets and a circular divided light medallion with the Great Seal of the United States etched in its glass center. Several versions of the Seal have existed, but this pattern is from the seal dating to the late 1800s. The Great Seal is also repeated in the hand knotted carpet inset of the blue carpet in the well of the courtroom.

The judges bench has been designed to have up to 22 judges. It is also used for other special proceedings and naturalizations on occasion. The portrait behind the judges bench is of the Honorable Orie Leon Phillips, who was one of the first judges for the Tenth Circuit. He served the judiciary from 1923, as a federal district judge for the District of New Mexico, to 1929 when he became a court of appeals judge for the Tenth Circuit. There he served for another 45 years until his death in 1974.

Courtroom Two

This courtroom was constructed, as was Courtroom 1, in space formerly occupied by the post office's counter area and workroom. That space was used to serve the public and to sort mail. This courtroom is designed as a "en banc panel" type of appellate courtroom used by three judges to hear cases on appeal from the trial courts of the Tenth Circuit.

It is smaller than its companion Courtroom 1, by drawing the walls in, thereby "attached" to the columns. Daylight was brought into the large, open work area by the skylight above, like Courtroom 1's. A luminous ceiling separates the courtroom from the original skylight opening. The grid work from the ceiling is derived from the decorative ceilings that were used in public structures of prominence, circa early 1900s. The grid work, glass and faux onyx are new construction. Each of the six states of the Tenth Circuit are represented by a State Seal etched into the glass panel above.

The painted plaster and wood detailing, although new, is based on Neoclassical or Classical Revival architectural style. The main entry's stone was selected to emphasize the portal and the importance of the room. Figured oak and a bronze Greek key motif add ornamentation and detail to the doors.